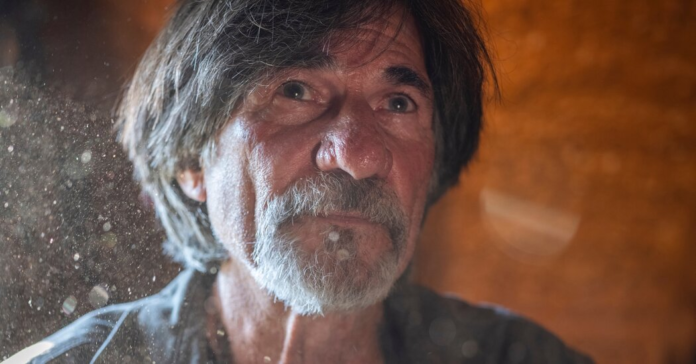

But Fisk, who is 77, can be notoriously difficult to entice to a film. Since 1970, he has designed relatively few; at one point, he took nearly 20 years off. When Scorsese approached him, Fisk was excited by the opportunity to collaborate with the director, but also by the chance to excavate a world rarely depicted onscreen: The film takes place in a sliver of lost time, one wedged between more familiar depictions of Native Americans in the 19th century and the well-worn imagery of the Roaring ’20s. Bringing this moment of cultural collision back to life would represent as sweeping a challenge as Fisk had ever faced. The story unfolds in about 40 sets, as varied as Masonic lodges, Osage funerals and federal courtrooms, spread over a million acres and costing about $15 million of the film’s $200 million budget. The sets would represent a kind of culmination of Fisk’s careerlong obsession with reclaiming the rough contours of American history. More than any one aesthetic vision, he has sought over a half century to scour away the visual clichés that mar films, seeking beneath them the vivid woodgrain and forgotten colors of the past.

If Fisk’s name isn’t recognizable to most Americans, his imagery has shaped our collective understanding of what a modern historical epic looks and feels like. His signature is the 360-degree construction of the outdoor set, believably inhabited and painstakingly aged, marrying an anthropological eye for period detail with a rough-hewed naturalism that can edge, at times, into the slippery atmosphere of a dreamscape. For “There Will Be Blood,” he erected a 100-foot oil derrick, following turn-of-the-century blueprints so that it might take on a more ragged, credible shape, planting it atop a barren hillside that framed it against the sunset with painterly flair. In “The Revenant,” Iñárritu’s drifting, magic-inflected survival epic about a 19th-century fur trapper, Fisk scouted snow-buried valleys deep in the Canadian Rockies, throwing up post-and-beam forts in settings so sublime that the film exudes the mind-silencing cold of the characters’ icy journey.

But Fisk’s work is perhaps most unmistakable as the backdrop behind the films of Terrence Malick, whose swirling, voice-over-driven narratives find grounding in Fisk’s elemental settings: oceanlike wheat fields, serene jungle villages, a mother’s kitchen at twilight. It’s a fusion of styles the two filmmakers began exploring in “Badlands” (1973) — the open-road thriller where Fisk met his wife, the actress Sissy Spacek — and have continued over four decades. As interested as Fisk is in historical authenticity, his work with Malick and others is driven by a desire to build “for character and through character,” designing sets that manage to convey, in the manner of poetic compression, a film’s emotional core. Malick rarely writes a conventional script, and Fisk never shows the director any designs, an improvisational partnership that seeks to capture fleeting aspects of human existence otherwise hard to render through conventional narrative: grace, transcendence, communion with nature. On set, Malick refers to Fisk as “my eyes.”

Fisk has a background in the fine arts, but he considers himself more strictly speaking a “worker” — the conduit of someone else’s vision. As a production designer, he is in charge of manifesting a film’s reality, interpreting the fluid laws set by the director and script, in order to bring its world into physical existence. A designer must not only come up with all the textures, colors and moods of this world but also figure out how to engineer it all on budget, marshaling a machinery of illustrators, prop makers, location scouts and set decorators. A movie’s magic often comes down to how well a designer can trim a script’s price tag in labor and materials without sacrificing its aesthetic. (Noirs of the 1940s are crosshatched with shadows partly to conceal threadbare sets.) It is a vast undertaking of dramatic invention — one that aspires to be seen, though never noticed. When people say they love a film’s cinematography, what they often mean is its design: what they see within the frame, rather than the way it was captured.

Until recently, no tidy educational pipeline existed to produce this skill set; designers tended to emerge from whatever field corresponded to the demands of filmmaking at the time. In early Hollywood, most were painters, hired to illustrate literal backdrops on massive rolls of canvas hung behind the actors. As camera movements became more dynamic, so did the artwork, expanding to include full-scale replicas and miniature models, the provinces of architects and sculptors. During the studio era, backlots and prop shops supplied an interchangeable conveyor belt of artifice, with each studio employing a head designer to curate a kind of house style. Once the French New Wave and others pushed production outdoors, embracing unvarnished cityscapes, designers also became anthropologists, hunting for spaces that evoked the right reality. Even the title “production designer” itself is an expression of one designer’s ever-expanding duties on one film: David O. Selznick gave it to William Cameron Menzies after he conceived and constructed several groundbreaking set pieces in “Gone with the Wind.”